Belief Before Biology

When effort, meaning, and imagination stretch the body beyond its “limits.”

On May 6, 1954, Roger Bannister did the impossible. He ran a mile in 3 minutes and 59 seconds – a feat experts had declared physiologically out of reach. The four-minute barrier had stood like a monolith for a decade, daring runners to touch it. None could. And then Bannister did.

Forty-six days later, John Landy ran 3:58. Within the next few years, more followed. Soon after, the floodgates opened. What had changed?

Probably not their VO2 max. Not their biomechanics. Their belief.

Before Bannister, the human imagination had placed a psychological fence around the four-minute mile. His run didn’t just shatter a world record; it cracked open the collective mindset of what was possible. And once one person proved it could be done, the dam broke.

In 1978, Reinhold Messner and Peter Habeler tried to become the first climbers to summit Mount Everest without supplemental oxygen. At the time, experts called it “certain suicide.” After enduring formidable conditions and being forced to crawl near the summit, the two men reached the peak on May 8. After the ascent, the dumbfounded experts rushed to reassess their claim and launched a major research expedition. Their determination: an oxygen-free ascent was possible, but just barely. Today, more than 200 climbers have done it.

In his book Endure, Alex Hutchinson writes,

“It remained an intriguing coincidence that the capacity of humans to survive in thin air should just happen to reach its absolute limit at the highest point on the planet. But given what we’ve learned about how finish lines and other endpoints influence the body’s safety circuitry, I can’t help but suspect that, if tectonic forces had given us a 30,000-foot peak instead of Everest’s 29,029, someone would eventually climb it without supplemental oxygen.”

A few weeks ago, Nike announced its latest audacious project: Breaking 4. On June 26, Faith Kipyegon will try to become the first female to run under four minutes in the mile. Just like Bannister, Messner, and Habeler, you don’t have to look very far to see the doubters and the critics.

That pattern keeps repeating. Most logical humans have a visceral reaction to something considered “impossible.” But logical humans aren’t the ones pushing new frontiers. That space is reserved for the dreamers.

This story isn’t just about the elites. In fact, if you look closely, the same psychological mechanics play out every weekend at local marathons worldwide. Barriers have a magnetic pull. Runners of all ability levels—dreamers in their own right—find a way to rise to them.

Barriers Built by Belief

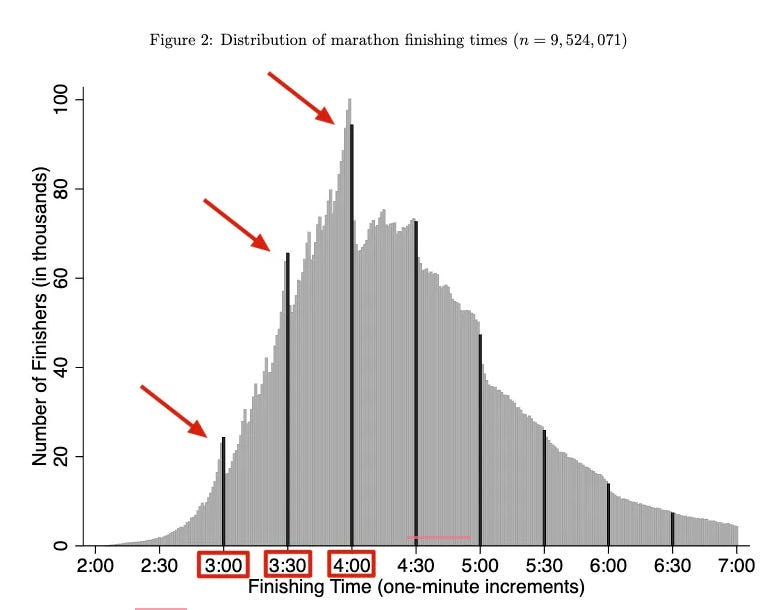

Picture this: you’re watching the finish line of a big-city marathon. The clock ticks past 2:59:00. Suddenly, a surge of runners comes barreling in. The number of finishers will predictably spike by more than 50% in that one minute alone. The same thing happens at 3:59:00 and 4:59:00, and so on.

A comprehensive dataset of over nine million marathon finishers graphically depicts these spikes—dramatic increases just before round numbers, followed by steep drop-offs right after. And yet, physiologically, there is no magical difference between 3:59:58 and 4:00:02.

So why does it happen?

Because the finish line isn’t just a physical threshold, it’s a psychological one. A barrier infused with meaning.

These round numbers become symbols of mastery, of legitimacy, of identity. And when we attach that kind of meaning to a goal, our brains allow us to dig a little deeper, suffer a little longer, and stretch a little farther than we thought we could.

The Muscle-Mind Feedback Loop

We often think of performance as dictated by our bodies—heart rate, muscle fatigue, lactate levels. But in truth, the relationship between brain and body is dynamic, not linear. Your legs don’t simply carry out commands. They negotiate with your mind.

The muscles will only perform to the extent that the mind is willing to cope (or feel inspired).

The mind says, “This is what I want.”

The body replies: “Here is what I can do.”

The mind pushes back: “What if we want it more?”

The result is a continuous feedback loop: perception of effort, emotional stakes, perceived danger, and actual capacity—all engaged in a complex dance.

This is why runners fade without obvious signs of physical breakdown. Why some athletes find miraculous kicks when the finish line is in sight. Why the impossible becomes possible when someone else does it first.

It’s not just about the muscles. It’s about meaning.

Redefining the Edge

Look at any distribution of marathon finish times, and it mirrors a normal bell curve, until it doesn’t. At those round numbers, the curve fractures. Performance becomes nonlinear.

That’s the mind’s fingerprint on the body.

It challenges the reductionist view that a biochemical equation can define performance. Athletic performance isn’t defined exclusively by what you’re physically capable of. It’s what you’re capable of within the context of the stakes, your tolerance for discomfort, and the incentives at play.

This leads to an uncomfortable but exhilarating truth: many of our limits are self-imposed. Not in a motivational poster way, but in a biological, neurological, measurable sense. The mind frames the outer limits of what we believe is humanly possible.

The governor of the system isn’t just the legs. It’s the brain. And that governor has a bias towards survival, not excellence.

Disabling the Default Setting

Some scientists believe the brain acts like a safety regulator that limits how much of your physiological capacity you can access, unless the perceived reward outweighs the risk.

Push too hard, and the governor shuts you down. But increase the stakes (real or perceived) and suddenly, the ceiling rises. Your true limit was always there, just obscured by protective wiring.

So the real question isn’t “how hard can you go?”

It’s: “What are you telling yourself about what’s at stake?”

Next week, we’ll dive deeper into the Central Governor Theory—what it means, how it works, and look at some fascinating examples of how people can hijack the central governor and reconfigure the inner circuitry of their mind.

If this made you think bigger, imagine what it could do for someone else? Share The Run Down and help ignite belief where doubt used to live. One share could spark a new starting line.