The neuroticism of distance runners (myself included) never ceases to amaze me. I’ve seen athletes do loops around parking lots to round their run up to an even 8.00 miles instead of finishing at 7.96. I’ve watched runners go out for an unplanned 10-minute Sunday evening double to exceed a certain mileage target. I’ve witnessed disappointment when a split is missed by two seconds, even if the workout was otherwise flawless. And I’ve seen athletes step into an ice bath with military timing. Ten minutes exactly, not a second more.

What all of these behaviors share is a belief, conscious or not, that adaptation is precise. That the body is akin to a machine with binary switches: hit the target, adapt; miss it, and the effort is wasted.

While understandable, this mindset is biologically false, and I’d argue that it can be psychologically harmful. The body does not deal in absolutes. It recognizes stress, not symmetry. The more you cling to precision, the more fragile you become.

What are you optimizing for?

Performance is maddeningly complex. We want it to be simple: hit this pace, run this mileage, eat these macros, achieve this VO2 max, and you will win. But the deeper truth is messier. Performance on race day isn’t a single metric you can master. It’s a composite of dozens of variables: physical, psychological, environmental, and tactical.

And yet, we cling to proxies, or surrogate markers of performance. Mileage. VO2 max. Blood lactate values. These might be determinants of performance, but they are not the same thing as performance itself. We act as if perfect alignment with these numbers is what unlocks excellence. But proxies are just that: approximations.

We treat workouts like sacred acts that must be performed just-so to earn the blessing of improvement. But here is the liberating truth. The body doesn’t require perfection. Every pace you run carries the potential signal for adaptation. A workout can be beneficial across a spectrum without needing precision.

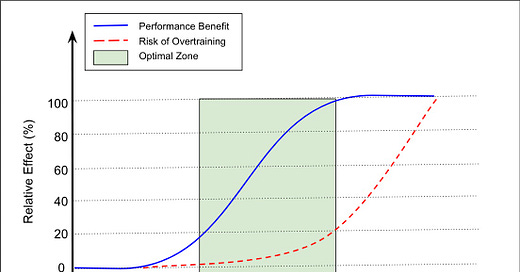

The graph above illustrates this principle. Performance benefits (blue line) increase with training stimulus but begin to plateau as the session becomes excessively taxing. Meanwhile, the risk of overtraining (red line) climbs steadily, especially beyond the optimal zone. The sweet spot is broad, not narrow. Adaptation doesn’t hinge on hitting the bullseye, but on staying in the general vicinity. You don’t need perfect; you need appropriate.

Perfect Data, Imperfect Reality

No trend has caught fire in recent years quite like double threshold training. Popularized by the Norwegians, the method involves two moderately hard sessions in one day rather than a single intense effort. The goal? Accumulate more time just below the lactate threshold, maximizing the aerobic stimulus without dipping too deep into anaerobic reserves.

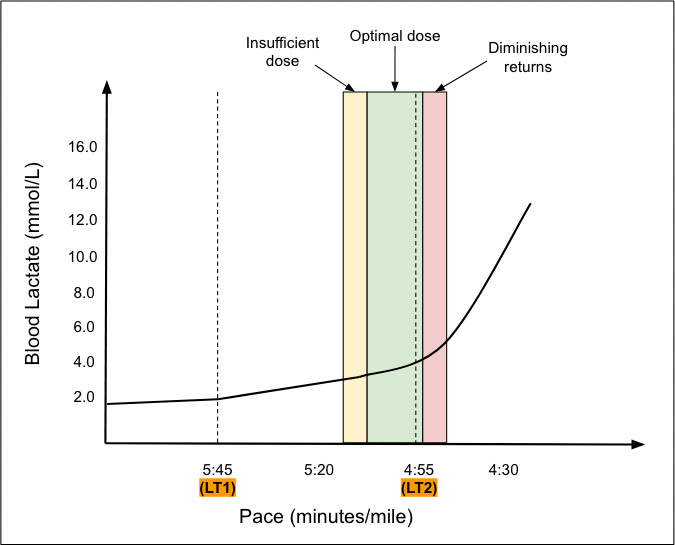

To hit this “just right” zone, athletes often stop mid-workout, prick their fingers, and measure blood lactate. If done correctly, they aim to stay just below the inflection point on the lactate curve, typically around 4.0 mmol/L of lactate. But “done correctly” is the operative phrase.

Here’s the problem: this kind of training rests on some key assumptions that don’t always hold up. It assumes your lactate curve today is identical to the one from your last lab test, even though variables like fitness, weather, altitude, and hydration can shift it. And it doesn’t account for common testing errors. A drop of sweat can dilute the sample. Key decisions that get made based on data in a workout might be outdated or wrong.

Are there differences between training at 7.0 mmol and 2.0 mmol of lactate? Of course. But between 2.8 and 3.2? Not really. There is a meaningful range, not a magic number. The body doesn’t care about decimal points. It responds to general signals, not fine-tuned settings.

Zone 2 training suffers from the same issue. Runners obsess over staying in a heart-rate window calculated by generic formulas based on age and max heart rate. But the boundary between Zone 2 and Zone 3 isn’t a physiological cliff; it’s a blurry spectrum. Five beats per minute doesn’t make or break adaptation, no matter what color your watch display turns, transitioning from one zone to the next.

Here’s what matters: the body follows the SAID principle—Specific Adaptation to Imposed Demands. Every pace creates a stimulus. Every effort sends a signal. Whether you’re running at 2.9 or 4.1 mmol/L, adaptation is happening. You might last longer at the lower intensity, but both contribute to growth.

To be clear, I’m not opposed to threshold training or using zones to guide workout prescription. As with all training methods, there are benefits and shortcomings. In this specific case, I’d simply argue that testing metrics such as zones and lactate are not a panacea.

Testing and monitoring imply that control matters most. But racing is chaos. Your job isn’t to become the best at hitting a number. It’s to prepare for moments when numbers go out the window.

There is no magic training zone that delivers outsized benefits. There are only paces that are more or less aligned with the goal of the session. More often than not, close is good enough.

Relying on precision creates more ways for the workout to fail

So far, we’ve explored why perfectionism in training clashes with biology. But there’s also a psychological cost when numbers start dictating meaning more than the experience itself.

I remember chatting with Coach Milt during the cross-country season a few years ago. He was describing a workout UNC had done on the American Tobacco Trail during a classic hot and humid North Carolina summer morning. One of the younger guys had an incredible session: he hung with the veterans and pushed into new territory in both volume and intensity. It was a clear win by any reasonable standard.

But that night, in his training log, the athlete wrote he was disappointed after evaluating the session on his Garmin App.

Why? He’d spent too much time in Zone 4.

Here’s the catch: in warm conditions, your heart rate is naturally elevated. The same effort feels harder, and your zones (especially if calculated from a temperature-controlled lab or an off-the-shelf algorithm) don’t necessarily hold up. Add in the sketchy reliability of wrist-based heart rate monitors, and it’s clear this athlete was anchoring his emotions to data that was both contextually flawed and practically irrelevant.

Perfectionism shrinks your field of vision. The tighter you grip the small stuff, the more likely you are to lose sight of what truly matters. Effort becomes performative. Progress becomes fragile. You start optimizing for metrics, not mastery.

Personal finance guru Ramit Sethi, who once guest lectured for my class at Stanford, explained this perfectly:

“Most people focus on the $3 decision (can I afford this coffee?) rather than the $30,000 questions (am I saving and investing appropriately?).”

His point? A handful of big decisions carry most of the weight. Nail those, and you don’t have to sweat the small stuff as much.

Don’t let the optimal get in the way of the beneficial

The same is true in training. A few foundational principles: consistency, appropriate effort, and good recovery will get you 95% of the way there. Whether your heart rate was 164 or 172 on a given rep matters far less than whether you show up again tomorrow.

You don’t need to grip the rudder so tightly to steer the ship. When you’re training with intentionality over months and seasons, minor errors will get flattened by the freight train of momentum. What matters isn’t perfection, it’s inertia in the right direction.

One single session rarely makes or breaks you. It’s the accumulation that counts. It’s the pattern that matters. In training, the big rocks build the foundation, not the grains of sand.

If this made you think bigger, imagine what it could do for someone else? Share The Run Down and help ignite belief where doubt used to live. One share could spark a new starting line.