The Science of A Taper

How shedding fatigue reveals your fitness and primes your body for peak performance

Most runners know that in the final weeks before a big race, they’re supposed to back off—less mileage, more rest, and a shift from “grind mode” to recovery mode. And yet that strategy feels very unnatural. For competitive athletes, rest is unnerving. Deep down, they worry that if they rest a little, they risk losing all the hard-won adaptations and will have a terrible race.

But here’s the paradox: if you want to race your best, you have to resist that instinct. I wrote all the psychological side of backing off in last week’s newsletter. A half-hearted taper doesn’t cut it. To unlock the fitness you’ve built, you need to commit fully.

This isn’t just coaching dogma. It’s rooted in physiology. In this issue, we’ll break down why the taper works and how to do it right. We’ll unpack the key ingredients: timing, volume, intensity, structure, and a few special considerations.

What is a taper?

Tapering is a technique designed to reverse training-induced fatigue without compromising the training adaptations. As discussed in this newsletter, training itself doesn’t immediately lead to better fitness. In fact, training can leave you feeling damaged, dehydrated, and depleted. Improved fitness lies on the other side of recovery (remember stress + rest = growth).

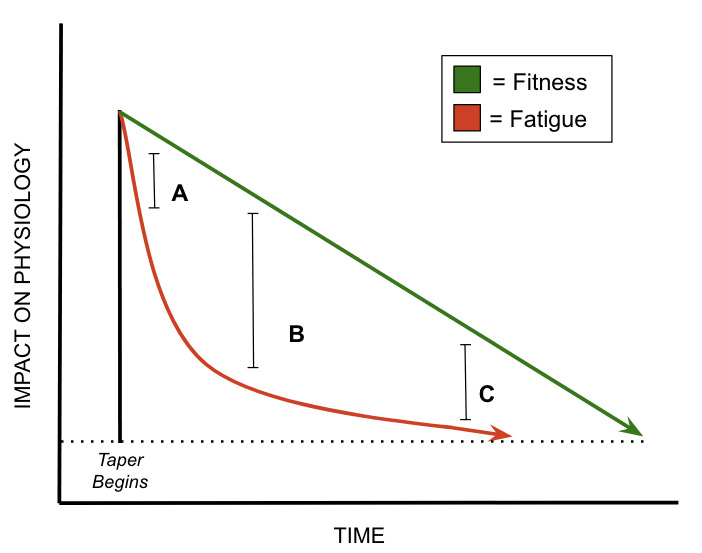

A helpful way to think about this is to separate the training response into two components: fitness and fatigue. After a big workout, you’re both fitter and more fatigued. Any runner who has raced a 5K or 10K knows this. You might have just learned you’re in the best shape of your life, but you’re way too tired to repeat that effort the next day. Your true fitness is masked by exhaustion.

Performance potential, then, is the difference between fitness and fatigue. Here is the key insight: fatigue fades much faster than fitness. Most experts suggest fatigue dissipates 2-5x quicker. Fitness is durable; fatigue is transient.

Think of fitness as the sun and fatigue as the clouds. The sun doesn’t disappear just because you can’t see it. It’s still there, waiting. The goal of the taper is to let the clouds part and let your fitness shine through at the right moment.

This graph illustrates a key principle of tapering: fitness declines slowly, while fatigue drops off much faster. At point A, there is still too much residual fatigue masking your fitness. Racing here would leave you underperforming because you’re legs haven’t had time to fully recover from hard training. At point B, you’ve shed enough fatigue to let the fitness shine through. Even though you might have lost a tiny amount of fitness, the gap between fitness and fatigue is at its widest. This is the sweet spot for performance potential. At point C, fatigue is fully gone, but you’ve waited so long that your body has begun to detrain. Fresh legs aren’t helpful if the fitness base you’ve built has started to erode. The goal of the taper is to hit point B.

What is happening in the body?

So why does the taper work? Under the hood, your body is performing remarkable repairs and fine-tuning.

Muscle glycogen stores refill, giving you a full tank of quick-burning fuel.

Blood plasma volume increases, improving cardiac output and cooling capacity.

Hormonal balance shifts, with testosterone rising relative to cortisol.

Fast twitch muscle fibers grow and become more explosive, boosting your power output.

Many athletes also report better sleep, improved mood, and a sense of freshness they haven’t felt in weeks.

Collectively, these changes can translate to a 2-3% performance boost, which is a margin large enough to decide races.

How long?

The sweet spot for most distance runners is 10-14 days. This gives your body enough time to shed accumulated fatigue while holding onto the fitness you’ve built.

For key championship races, a full two-week taper is common. This allows you to fully absorb the training and express your fitness on race day. For smaller tune-up races or lower-stakes efforts, a 7-day taper might be sufficient.

This graph shows how the timing of your training impacts race-day performance. Of course, it’s important to caveat that this is purely theoretical and not everybody responds according to these timelines.

When you’re 20+ days out from a goal race, hard workouts and higher volume deliver big returns. You’re far enough from race day that your body has time to recover and adapt. This is the “zone of maximal impact.” In this timeframe, building fitness is the primary objective because you have plenty of time to let residual fatigue dissipate.

As race day approaches, the payoff from hard training shrinks while the risk of carrying fatigue to the starting line rises. Within about 7-10 days, heroic workouts often do more harm than good because there is no time to recover fully. At this point, the goal isn’t to gain fitness. It’s to protect what you’ve already built.

Volume

When it comes to tapering, reducing volume is the single biggest lever you can pull. Of all the training variables (volume, intensity, frequency, and density), cutting back mileage has the greatest impact on race-day performance.

The science is clear: most studies showing performance gains from a taper involve a minimum reduction of at least 40% from peak training volume. For example, if you’re averaging 70 miles per week, your mileage should “bottom out” around 35-40 miles in the final taper week.

There is some nuance in how you reduce the volume. A progressive, non-linear taper works best. Rather than slashing your mileage in half overnight (a step taper), gradually trim the volume over 10-14 days. Compared with other options, the most effective approach supported by research is an exponential taper (seen below), where the largest drop happens early, followed by smaller incremental reductions.

Think of it as easing off the gas, not slamming on the brakes. The body responds best to gentle adjustments, not abrupt shocks to the system.

Frequency

When you cut volume during a taper, it doesn’t mean you should stop running altogether and start stacking up rest days. In fact, one mistake people make in the taper is reducing how often they run.

The key is to maintain your normal training rhythm, just with shorter runs.

Drop overall mileage by trimming 10-20% off your daily runs

Consider removing doubles that are in the program mainly to boost mileage

Consider skipping the long run in the final weeks

This meta-anslysis found a rule of thumb for elite athletes is to keep your frequency of weekly training relatively stable during a taper, and only drop it to about 80% of its normal level. So if you normally run 10 sessions per week (7 runs and 3 doubles), a good taper still includes 7-8 sessions. This keeps your neuromuscular rhythm intact and helps you avoid feeling sluggish.

Intensity

One of the golden rules of tapering: cut volume, not intensity.

Too many runners assume tapering means jogging easy for two weeks. But studies consistently show that maintaining intensity during a taper is critical for preserving fitness. If you back off the pace in your pre-race workouts, you risk losing the aerobic enzymes, neuromuscular sharpness, and muscle fiber recruitment you’ve spent months building.

The best approach is to keep your workouts fast and specific to goal race pace, but shorter in duration and with plenty of rest. You want to avoid doing sessions that dig you in a hole.

One study on cyclists found that athletes who maintained intensity but cut volume improved by 4.3% in a 40K time trial after a 7-day taper. Those who reduced intensity while preserving volume? No improvement at all.

The takeaway: during a taper, speed keeps you sharp, while excess mileage makes you stale.

Muscle Fiber Type

Here’s an interesting wrinkle: tapering doesn’t affect all muscle fibers equally.

Your slow-twitch fibers—the workhorses for steady aerobic efforts—are highly fatigue-resistant and stay robust even as mileage drops. But your fast-twitch fibers? They respond dramatically to a well-executed taper. These fibers are responsible for speed, power, and that finishing kick at the end of a race.

During a taper, fast-twitch fibers increase in size, contract more quickly, and produce greater force. In one study, swimmers who reduced their training volume by 50% over 21 days experienced a 4% performance improvement, largely due to the rejuvenation of fast-twitch fibers. Similarly, another study found that collegiate cross-country runners improved 3% after cutting their mileage in half for three weeks, with a 14% increase in fast-twitch fiber size and a 9% bump in power output.

That “pop” in your legs during race week isn’t just in your head—it’s your fast-twitch fibers finally firing on all cylinders.

Know When to Break the Rules

All of this explains why the taper works so well in theory. But training and racing aren’t theoretical. There are moments when experience, intuition, and competition push you to step outside the textbook.

During my junior year of high school, I raced five times in six days, culminating in the most important week of my running career to that point. On Monday evening, I tripled at the Connecticut state championships and then flew to North Carolina for New Balance Nationals two days later, where I ran two more events.

By any scientific standard, that wasn’t optimal. And yet, it was one of the most successful weeks of my career. My team won the state title, I won the 5,000m at nationals, and split a huge PR 4:06 1600 on tired legs in the DMR.

General principles matter—but so does knowing when to set them aside. The art of coaching and competing lies in holding both truths at once.

If this made you think bigger, imagine what it could do for someone else? Share The Run Down and help ignite belief where doubt used to live. One share could spark a new starting line.

Famously Sir Roger Bannister took 5 full days off from running before becoming the first human to break a 4 minute mile.

Something interesting I've noticed through my career personally is the fragility of aerobic fitness and the consistency of anerobic fitness. What I mean by this is that if I stop running for a month, strength and lactic buffering have a longer half life than my aerobic fitness. This was put on full display during my plebe summer at the Naval Academy.

I was 18 in Boot Camp. 6 weeks prior I had run a 1:51.13 at Brooks PR (PR). Then I went through 6 weeks of boot camp for the navy and ironically put on 13lbs. At the 'Plebe Summer Smoker', on an indoor track, I ran a 1:53.1. Absolutely no running training for 6 weeks. If you asked me to do the equivalent for 5k, no shot. At least for me.

Just interesting, no factual or data driven aniqudotes over here, just observation 😂.

What an incredible article Alex! The information I glean from you, with all your articles, is par none! Keep at

It. Catherine A.