Why Your Dinner Plate Might Be Your Best Injury Prevention Tool

What successful runners know about food, fueling, and staying in the game

It always starts the same way.

A dull, imperceptible ache in your shin, hip, or foot. It’s easy to explain away, and easier to train through. A few days pass. Maybe a week. The discomfort lingers. It shifts from vague to specific, from annoying to concerning. Most runners reach for their foam roller, blame it on a tight muscle that “won’t warm up,” and keep logging miles.

Until they can’t.

Eventually, the pain overshadows everything. It hurts to walk. It throbs at rest. By the time you’re in the orthopedist’s office or in the MRI machine, you’re hoping for an answer to your misery. Then the words land: stress reaction… or worse, stress fracture.

I’ve heard them too many times myself.

For distance runners, bone injuries feel like a betrayal. They don’t announce themselves. They sneak up on you when it’s least expected. That’s what makes bone injuries so cruel: they don’t test your effort; they test your foundation. And if the foundation is flawed, it doesn’t matter how hard you train.

Here’s the simple truth: while bone injuries can feel unpredictable, they are rarely unpreventable. And the missing piece isn’t just in your training, it’s also in your fueling.

My hope is that most readers never experience a bone injury. But if you have, you know how disruptive they can be, sidelining training for months, often without warning.

Why This Matters

Stronger bones won’t directly shave seconds off your 5K—but they might be the foundation that allows everything else to work.

And beyond performance, bone health matters for life. Peak bone mass is typically reached between the ages of 20 and 25. After that, hormonal changes make it harder to build bone and easier to lose it. Repeated bone stress injuries during adolescence or early adulthood can chip away at the reserves meant to protect you later on.

What makes this even more urgent is that the nutritional decisions you make now, especially during periods of high training, directly impact how strong or fragile your skeleton will be years in the future.

Humans are notoriously bad at responding to risks that don’t offer immediate consequences. It’s easy to ignore until it’s too late. But if you’re a runner who plans to be active for life, you can’t afford to treat this like an afterthought.

This isn’t about fear-mongering. It’s about risk management. We buckle our seatbelts even if we’ve never been in a crash. We keep fire extinguishers in kitchens that have never burned. The same logic applies here: the downside is too high not to act.

Check out last week’s newsletter for my perspective on protecting yourself from downside risks.

Defining the problem

Bones aren’t static. They’re dynamic, living tissue that constantly remodels in response to stress. Every run causes tiny amounts of microdamage. That’s not a flaw; it’s the trigger for growth. Specialized cells called osteoclasts clear out the damaged areas, and others called osteoblasts rebuild stronger bone in their place.

This cycle is why impact, in the right dose, makes bones stronger, not weaker. In fact, on average, runners tend to have stronger bones than cyclists or swimmers because we engage in an activity with a powerful osteogenic stimulus (bone-building activity). However, this is only true if the recovery and nutrition behind the scenes are sufficient to support the repair.

Problems arise when breakdown outpaces repair. Too much training, too little recovery, or inadequate fueling can tip the balance. That’s why stress reactions and, eventually, stress fractures occur.

What makes bone injuries particularly insidious is their delayed feedback loop. Bone turnover is slow. While tissues in your gut lining regenerate in days, bones take weeks. Osteoclast activity alone can span 3-4 weeks to initiate the remodeling process. So a sudden and sustained spike in mileage might not show up as pain until nearly a month later, when it’s already too late.

That’s the challenge: you don’t get immediate warning signs. You have to manage risk, not just respond to symptoms.

The Hidden Culprit: Fueling

When runners get hurt, most people look at the usual suspects: training volume, running form, and shoe choice. There’s nothing wrong with that. But perfect form or expensive shoes won’t be your savior. In fact, one of the most powerful drivers of bone injury isn’t mechanical. It’s metabolic.

If you’ve ever wondered what your dinner plate has to do with your tibia or femur, you’re not alone. I didn’t see the connection either, especially in high school. But looking back, it’s clear. The three bone injuries I had as a teenager weren’t just bad luck. They were the predictable consequence of unintentional under-fueling.

Most mornings in high school, I grabbed a light breakfast on the way out the door. Hours would pass between lunch and my next meal after practice. I ate what I thought were “healthy” foods, but gave almost no thought to timing or total intake. I didn’t understand how critical carbohydrates and protein were for recovery after hard training. Beneath the surface, my body was quietly rebelling.

Your body on a budget: What happens when you’re in a caloric deficit?

Think of your body as running on a budget. Calories are currency, and your body spends them strategically. The organs that support life-sustaining function (heart, lungs, brain) always get paid first. Only after those basic needs are met does your body “fund” what it sees as non-essential systems.

If you’re in a consistent caloric deficit (burning more than you consume), your body starts making trade-offs. It cuts from the non-essentials. Bone health is one of the first things to go.

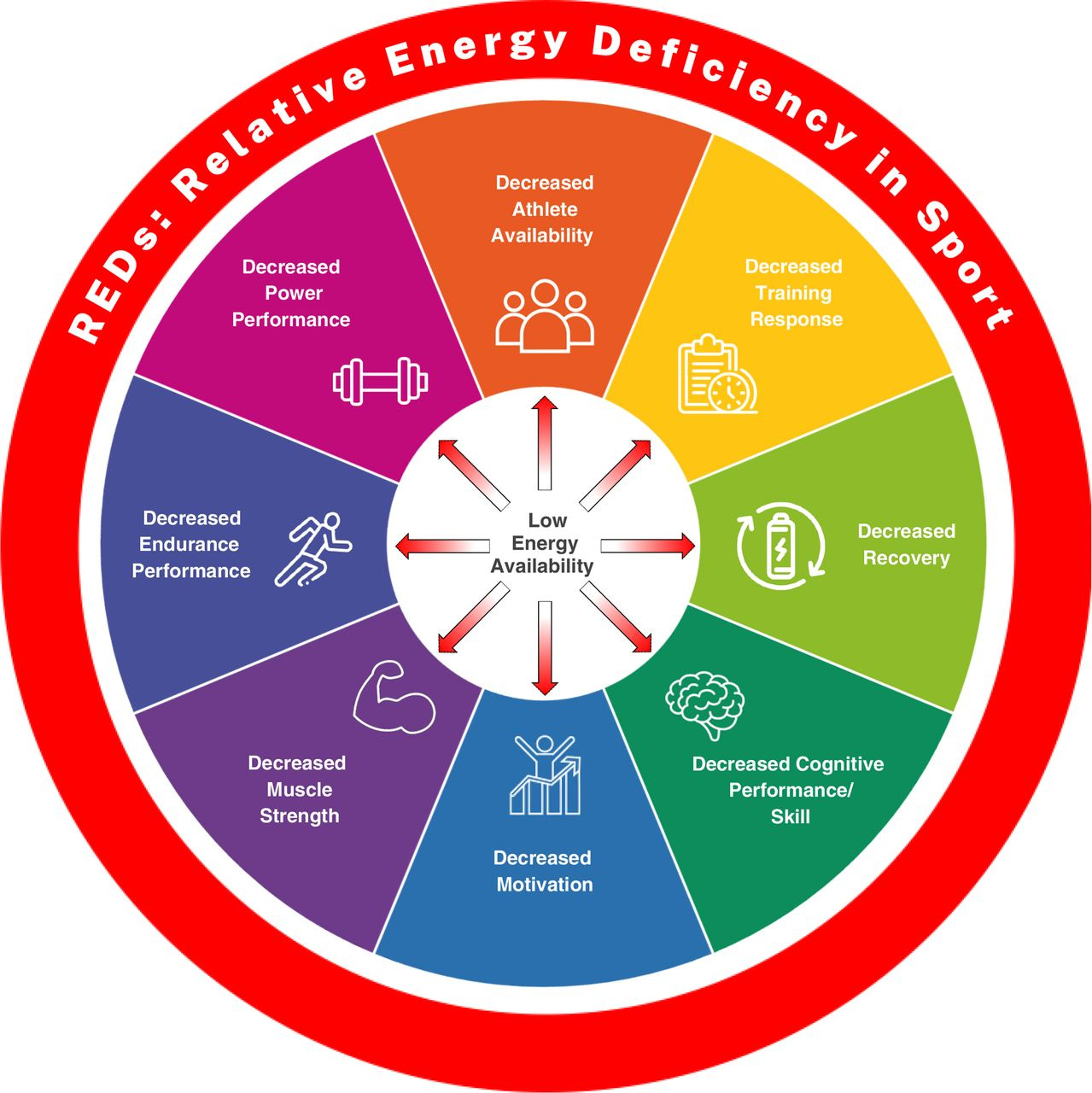

This is the core of Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S), a state where energy intake doesn’t meet the combined demands of training and basic function. Previously known as the female athlete triad, RED-S is now recognized as a broader syndrome affecting both men and women. It touches nearly every system in the body, but bones are particularly vulnerable. Research indicates that even 3-5 days of low energy availability increases bone resorption markers, slowly eroding bone density.

Most of the time, RED-S isn’t diagnosed directly. It’s a puzzle that clinicians piece together after ruling out other causes. But the body leaves clues. Here’s what to watch for:

Hormonal red flags. Missed or irregular periods in women, or low testosterone in men. These changes are linked to a 4.5x higher risk of bone injuries.

Frequent bone injuries (especially in the sacrum or femoral neck). These bones are particularly sensitive to under-fueling because they are rich in trabecular bone, which is highly metabolically active and dependent on adequate fuel.

Chronic fatigue. When fuel is scarce, your body conserves energy. That leaves less for movement, recovery, and performance.

Cold all the time. Underfueling reduces thyroid function, which drops your core temperature and slows your metabolism.

Mood swings or irritability. Low energy availability disrupts hormones and neurotransmitters that help regulate mood.

Getting sick often. A suppressed immune system is another casualty of underfueling.

Training hard but regressing. Without fuel, your body can’t adapt to the work you’re putting in.

Evidence-Based Solutions

Here are eight high-impact strategies I recommend to any athlete dealing with (or hoping to avoid) a bone stress injury. This isn’t medical advice, but it reflects the best of what I’ve learned through research, experience, and working with medical professionals.

1. Eat enough, always. If you’re going to miss, miss on the high side. The “risk” of being slightly over-fueled? Maybe two extra pounds of functional mass on the starting line. The risk of underfueling? Watching your championship race from the sidelines in a boot.

2. Prioritize Carbs. Carbs aren’t just fuel; studies show that carbs directly support bone formation and reduce bone breakdown more than any other macronutrient. My opinion is that training sessions should be “wrapped” in carbohydrate. Fuel beforehand, and eat soon after finishing.

3. Don’t backload your calories. As much as possible, space out your meals and snacks. Research has indicated that spending long periods of time in a caloric deficit is harmful to hormonal health. Your body can’t “catch up” by eating all of your calories at dinner.

4. Fuel during workouts. A sports drink or carb mix (like Gatorade, Skratch, or Maurten) during longer or more intense training sessions can shrink the window of time you’re in an energy deficit and protect bone health.

5. Eat energy-dense foods. Salads are loaded with nutrients and fiber, but tend to make you feel full without supplying enough calories per bite. Aim for foods that pack both nutrients and calories (think: nuts, oils, avocado, rice, potatoes). And if you’re in a pinch, eating a donut is better than putting yourself in a caloric deficit.

6. Take a rest day. One day off per week can be very protective for bones. It allows the body to make repairs and gives your osteoclast cells a chance to catch up to the training load. This is one of the most effective ways to hedge against the risk of a bone injury.

7. Monitor bloodwork. Get tested for markers like ferritin, cortisol, IGF-1, estradiol (females), testosterone (males), vitamin D, TSH, free T3, and T4. These biomarkers, especially when ordered and interpreted with a sports medicine physician or endocrinologist, can reveal signs of low energy availability before injuries happen.

8. Supplement if needed. Aim for a food-first approach to getting your vitamins and micronutrients. However, supplementing with calcium and vitamin D can be helpful if you’re deficient.

If you want to learn more, check out this Running Effect episode for more practical solutions on this topic.

Eat To Stay in the Game

I’ve had the privilege of being around athletes who have thrived well into their 30s and seen others flame out before graduating from college. One key difference? The ones who stayed healthy fueled like it was part of their job. Because it is.

I believe that one of the strongest predictors of career longevity is what (and how much) food is on an athlete’s plate at meal times. Those who skimp at dinner rarely last long in the sport.

You can train smarter. You can sleep more. But if you’re under-fueled, none of it sticks. Don’t forget that food is medicine.

If this made you think bigger, imagine what it could do for someone else? Share The Run Down and help ignite belief where doubt used to live. One share could spark a new starting line.

Another outstanding article by Alex Ostberg. His insights are consistently compelling, and I find myself eagerly anticipating each new piece he publishes. Catherine A.

How would you recommend dosing? Just finished a 5 mile run, and mixed 20 g of carbohydrates with water. I typically would take this about 30 minutes prior to the run, but after reading this article, I thought about trying it post run. With the idea of “wrapping” the run in carbs, maybe I take it prior to and post run…although that feels like a lot from a supplement mix. That said I don’t want to eat prior to a run…so maybe the answer is carb mix prior, natural carbs after.

Do the types of calories matter? I don’t know if I’m ever in a caloric deficit but I feel like strategizing around when I supplement protein and carbs make a difference. 😂🤪🙃