If a wearable device or recovery test exists, I’ve probably tried it. I’ve tracked blood biomarkers, HRV, sleep stages, morning heart rate, body temperature, grip strength—you name it. As a self-proclaimed optimizer, I chased the dream of a daily dashboard that could tell me exactly how recovered I was, how close I was to injury, or whether my training was working.

But the insights never came. Despite faithfully tracking every metric and analyzing trends, the data started to feel more like a random number generator. My readiness scores often seemed arbitrary, and sometimes, they were wildly misaligned with how I actually felt.

My breaking point came with a high-end sleep monitor, the kind used by Olympic athletes, which I was gifted by a physiologist associated with USATF. I slid it under my mattress, hoping it would reveal the final missing piece. But as I lay in bed that night, I found myself trying to sleep well, stressing over every toss and turn. By morning, the device flashed red: poor sleep, unfit to train. It hit me then—recovery, something meant to be restorative, had become performative. The gadget meant to help me get more relaxation was now the source of tension. I unplugged it the next day.

Why Data Provides False Security

Despite the allure of wearables, I’ve yet to find a device that meaningfully solves the problem of measuring recovery or training readiness. The promise is seductive: objective data, personalized insights, and smarter training. But technology often lures us into mistaking what’s measurable for what matters. Those two are rarely the same.

Recovery is messy. As William Sands, who has studied overtraining for years, says, “All recovered athletes are the same, but each unrecovered athlete is unrecovered in his or her own way.” His point? The human response to difficult training is highly individual, physiological, psychological, and musculoskeletal. No wearable captures all of that nuance.

Most devices focus narrowly, often leaning heavily on heart rate variability (HRV). While HRV is useful (especially for detecting cardiovascular strain) it says little about soreness, injury risk, or psychological burnout. It’s one piece of the puzzle, not the whole picture.

We also need to question how much precision we actually need. Do you really need to know you slept 6 hours and 12 minutes? Or is it enough to know you had a short night and adjust accordingly? Many products seem designed for the “worried well”—people who are healthy but increasingly anxious because of metrics they barely understand. Just because something can be measured doesn’t mean it should be.

Too often, recovery becomes another job. If recovery becomes work, then it’s no longer recovery. It’s just more stress.

Before You Track Data, Ask These Questions

Now, before I invest in any new metric or device, I ask three questions:

Is it meaningful? Does it track something that actually influences health or performance?

Example: Tracking resting heart rate might be meaningful because elevated values can reflect accumulated stress or illness. In contrast, tracking step count isn’t too meaningful for a distance runner who is already logging structured mileage.

Is it actionable? Will the output change what I do?

Example: If you are meticulously gathering data without making any meaningful changes to training, then the data becomes noise.

Is it novel or non-obvious? Does it tell me something I didn’t already know—or could just feel?

Example: Discovering that your HRV drops two days in a row at the same time your throat felt a little scratchy could help you differentiate if you lost your voice from singing at a concert versus catching an infection early. But being told you drained your battery after an interval session? You already knew that.

If the answer to any of these is “no,” I move on.

Don’t Outsource Your Awareness

Wearables offer a tidy convenience. They gamify recovery, delivering a daily readiness score, and promise precision. But in doing so, they risk numbing us to the more powerful feedback system we already have: our own awareness. Our obsession with objective data monitoring anesthetizes athletes to their internal clues.

Our bodies are remarkably sophisticated. Without a single algorithm, we integrate muscle soreness, mental energy, motivation, sleep quality, and life stress into one simple signal: how do I feel today? That internal barometer is doing exactly what wearables try (imperfectly) to replicate. But it’s far more holistic.

Christie Aschwanden, the author of Good To Go: What the Athlete in All of Us Can Learn from the Strange Science of Recovery, dedicated an entire chapter of her book to this concept of searching for this “magic metric.” She wrote:

We tend to think objective measures are more reliable or scientific than subjective ones. If we want to know how fast a car goes, the speedometer provides a more reliable indicator than the driver’s subjective feeling of the vehicle’s speed. But recovery is a far more complex phenomenon than speed.

Why Subjective Measures Matter

In my own training, wearables rarely told me anything I didn’t already know. After a grueling session, I felt fatigued. I didn’t need a device to tell me that. Learning to read those signals in real time, and adjusting accordingly in the hours and days that follow, has been far more useful than any algorithm’s rigid prescription.

As the old saying goes: not everything that counts can be counted, and not everything that can be counted counts.

The science backs this up. A 2015 review by Australian sports scientist Anna Saw examined 56 studies on training load and recovery. Her conclusion? Subjective measures (like mood, fatigue, and stress) were more sensitive and consistent than objective metrics. Increases in training load were reflected more reliably in how athletes felt than in changes to HRV, hormones, or blood markers.

A Sports Medicine review paper from 2022 echoed that sentiment. Self-reported wellness scores (sleep quality, soreness, and mental fatigue) strongly predict injury and overtraining risk. When these signals are ignored in favor of a green light on an app, athletes may miss critical windows to pull back before breakdowns occur. The paper concluded that “subordinating decisions to technology can mislead coaches and dull their attentive instincts.”

Another study followed 75 adolescent female soccer players over a season, recording their daily training load and wellness (mood, fatigue, stress, soreness, and sleep) alongside injuries. The researchers found that injuries were not only directly linked to higher training load, but also when their mood was significantly worse. The key takeaway is that an athlete’s subjective well-being can flag increased injury susceptibility.

Perhaps most importantly, what no wearable can measure is life context. I’ve seen countless athletes hit breaking points not because of physical overload, but because of emotional stress—family strain, academic pressure, or personal hardship. When life demands more, recovery capacity decreases, and performance suffers. No wristband can account for that.

How To Maximize Your Wearable Device

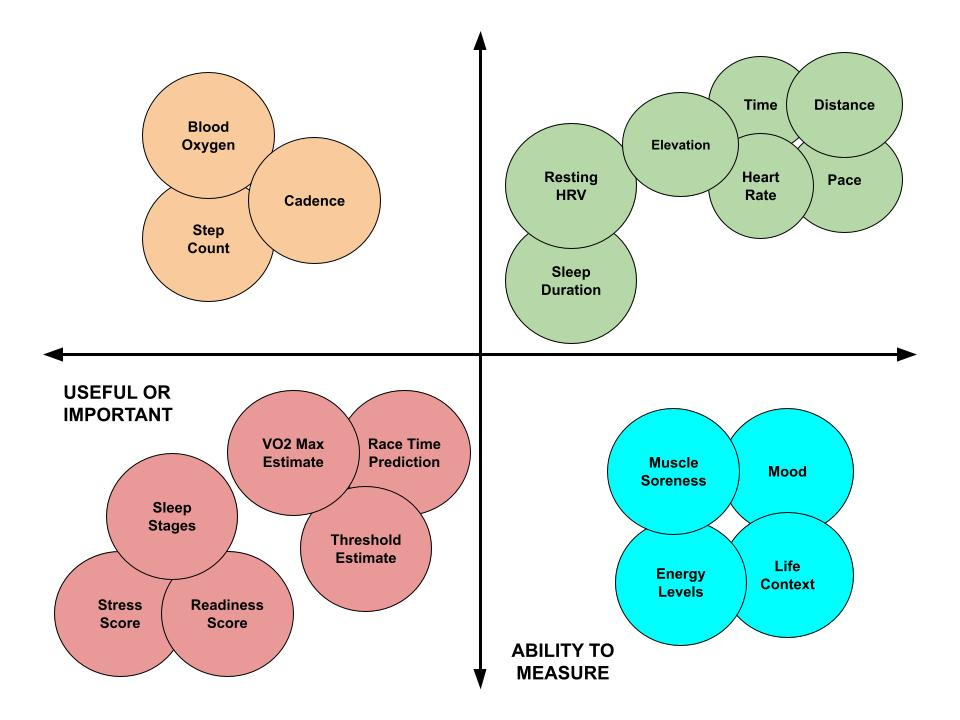

If you’re going to use a wearable, start by focusing on the metrics in the green quadrant. These are the basics: time, distance, pace, heart rate, and elevation. Use these confidently. Most devices these days are also fairly accurate in measuring resting HRV and total sleep time.

The blue quadrant is where wearables fall short. Markers like mood, soreness, energy, and life stress are essential to performance and recovery, but they can’t be captured by a sensor. No algorithm knows if you’re going through a breakup, lost sleep over work stress, or just feel mentally off. That’s your job. Cultivate the skill of checking in with yourself honestly.

Be especially cautious with the red quadrant: things like VO₂ max estimates, readiness scores, and race-time predictions. They’re often neither accurate nor actionable and typically rely on black-box algorithms that companies don’t disclose. At best, they’re loosely informed guesses; at worst, they can distract or mislead.

Finally, the orange quadrant includes data that’s easy to collect but not especially useful. Don’t confuse ease of measurement with relevance. Just because a device tracks something doesn’t mean you need to track it too.

No Number Knows Your Body Better Than You Do

Wearables can be helpful if you use them with a purpose. But if you strap one on without a clear goal, you risk drowning in data and mistaking noise for signal. As Seneca put it, “If you don’t know what port you’re sailing toward, no wind is favorable.” Without intention, even the most advanced tech won’t steer you in the right direction.

The best use of wearables isn’t to replace your intuition, but to refine it. Use them to ask better questions, not to deliver final answers. When objective and subjective signals align, they reinforce one another. When they diverge, trust your body first and investigate why. Jeff Bezos was famous for saying, “The thing I have noticed is when the anecdotes and the data disagree, the anecdotes are usually right.” That holds in training, too. Trust your lived experience more than a number.

I’m not anti-technology. With smarter algorithms and richer data, wearables may someday offer deeper insights. But for now, we have to respect their limitations. A single metric is meaningless without context. What matters is the trend, the story, the nuance.

I once believed recovery was something to measure. Now I know the best device for monitoring training is the one between your ears.

If this made you think bigger, imagine what it could do for someone else? Share The Run Down and help ignite belief where doubt used to live. One share could spark a new starting line.